The stories we tell ourselves

This post is a little different than my other ones because it started out as an journal entry (I sometimes journal on personal topics as a way to process and refine my thoughts). In this case, I thought I’d share it publicly in case someone else finds it helpful.

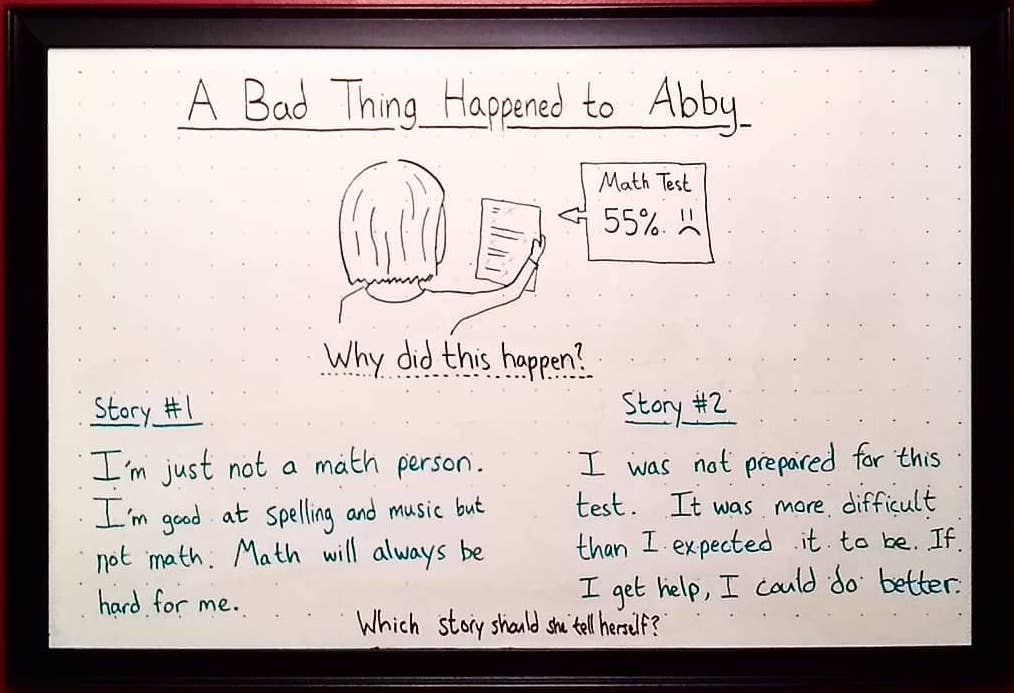

The stories we tell ourselves provide a frame of reference. Things happen everyday, but our stories help us decide whether we are ok or not ok. They help us answer the question “but what does it mean?”

Winning the lottery, failing a test, getting promoted, or getting fired. Any event can be interpreted as an incredible windfall, a terrible setback, or a neutral incident, all depending on the story. As Hamlet said, “…there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.”

Fragile stories

Some stories are more fragile than others. They make our happiness depend on external circumstances. Somebody is rude to us and we’re fuming for the rest of the day. Or something happens in the news and we fall apart.

David Foster Wallace, describes a number of fragile stories in his commencement speech, This is Water:

“If you worship money and things — if they are where you tap real meaning in life — then you will never have enough. Never feel you have enough. It’s the truth. Worship your own body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly, and when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally plant you… Worship power — you will feel weak and afraid, and you will need ever more power over others to keep the fear at bay. Worship your intellect, being seen as smart — you will end up feeling stupid, a fraud, always on the verge of being found out.”

These values seem so obviously bad that we’d never think of ourselves adopting them. Me? Worshiping power?

The problem is that these values slowly form without us even realizing it. David Foster Wallace continues:

“The insidious thing about these forms of worship is not that they’re evil or sinful; it is that they are unconscious. They are default-settings. They’re the kind of worship you just gradually slip into, day after day, getting more and more selective about what you see and how you measure value without ever being fully aware that that’s what you’re doing.”

Our stories form around us and we don’t even know that it’s happening.

Self-awareness

So how do we become more aware of the stories we are telling ourselves today?

I think that, somehow, we have to look at our life from an outside perspective.

When we reflect on our past experiences, it’s not that difficult to see the narratives we were following in hindsight. That’s because we’re seeing ourself as an observer.

There are probably ways to do something similar for our current self. James Clear once recommended the following exercise, “If you met someone exactly like yourself (same experience, same resources, same problems)… what advice would you give them?”

Journaling around questions like this, or asking people close to you are probably steps in the right direction.

Deliberately choosing robust stories

There’s a reason to be aware of our stories: it’s so we can change them when they aren’t working for us.

Consider this example from Victor Frankl’s “Man’s Search for Meaning”:

“Once, an elderly practitioner consulted me because of his severe depression. He could not overcome the loss of his wife who had died two years before and whom he had loved above all else. Now, how could I help him? What should I tell him? Well, I refrained from telling him anything but instead confronted him with the question, “What would have happened, Doctor, if you had died first, and your wife would have had to survive you?” “Oh,” he said, “for her this would have been terrible; how she would have suffered!”. Whereupon I replied, “You see, Doctor, such a suffering has been spared her, and it was you who have spared her this suffering — to be sure, at the price that now you have to survive and mourn her.” He said no word but shook my hand and calmly left my office. In some way, suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning, such as the meaning of sacrifice.”

All it took was a new story—a better story—and everything changed.

Imagine how much better our lives could be if we could deliberately choose our stories, instead of adopting whatever random narratives drift across our news and social media feeds. We’d have this powerful tool for helping us overcome obstacles and break out of bouts of unhappiness1.

Derek Sivers talks about how choosing our stories can drive us to action:

Actions come from emotions. Emotions come from beliefs. So choose whatever belief makes you take the action you want.

One belief makes you act selfish. Another belief makes you act generous. One thought makes you do something stupid. Another thought makes you do something smart. What matters is the action they create. So choose the thought that works for you.

This is a great way to summon up motivation but it’s a double-edged sword. Stories that drive us to action can just as easily drive away happiness. As Naval Ravikant said, “Desire is a contract that you make with yourself to be unhappy until you get what you want.”

So what’s an ambitious person to do? If an athlete lets go of the need to win (in order to be happy), will they lose their edge? If it’s your life’s pursuit to win the Nobel prize, is the chance to achieve it worth the lost happiness along the way? I don’t know.

Ultimately, robust stories don’t depend on outcomes. Inherent value is robust. Growth mindset is robust. Gratitude is robust. So is the belief that all experiences provide something valuable to teach us.

Perhaps the most robust story we can adopt is none at all:

“For all species other than us humans, things just are what they are. Our problem is that we’re always trying to figure out what things mean—why things are the way they are. As though the why matters. Emerson put it best: “We cannot spend the day in explanation.” Don’t waste time on false constructs.”

― Ryan Holiday, The Obstacle Is the Way

I used to hate the phrase “It is what it is.” It always seemed like a defeatist rejection of responsibility. But maybe it’s really about accepting reality as it is, and giving up the impulse to create an unnecessary story about it.

Self-manipulation

At first this all seems pretty empowering. If I’m unhappy with my current situation, I can just deliberately search for a better story to tell myself. It’s simple and inexpensive.

But isn’t this just self-manipulation? And isn’t that wrong somehow?

Naval Ravikant talked about this on his podcast:

“The beauty of being mentally high functioning in our society is that you can trade it for almost anything. You can be happy and smart—it’s just going to take more work. If you’re smart, you can figure out how to be healthy within your genetic constraints and how to be wealthy within your environmental constraints. If you’re smart, you can figure out how to be happy within your biological constraints.”

Doctors still take medicine when they are sick. It isn’t “self-manipulation.” It’s doing what gets results because you want the results2.

We should think of our mental health in the same way. If we’re too proud to deliberately choose new narratives when our old ones aren’t working, we hurt ourselves for no reason.

Knowing when to act

I never really think about my stories when things are going well. It’s only when my mental health is poor that I’m forced to do some digging.

It’s when I’m in a rut that I can’t seem to get out of, or fighting discouragement that doesn’t seem to go away. Whenever my mental state is like a wound that doesn’t seem to heal, it’s a good sign that there’s something in there that needs to be fixed.

Exercises

- What are the stories I have been telling myself?

- Are any of my stories fragile?

- What stories are contributing to my unhappiness?

- Why am I afraid to let go of these stories?

- What are some other stories I could tell?

1: This is basically reframing, a key part of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy that's shown to be widely effective

2: See also the philosophy of Pragmatism