Generalizing vs Specializing

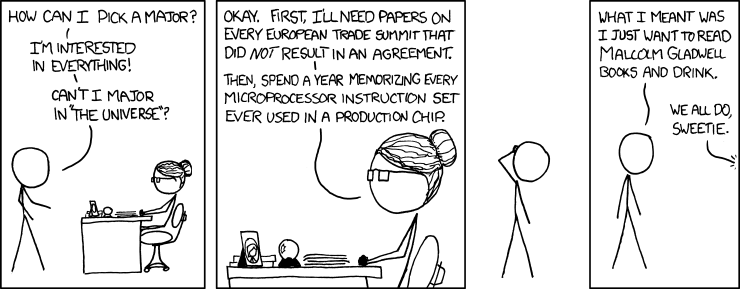

Do you ever feel like you are interested in everything? Like you can’t possibly settle down and pick one thing that you’ll end up doing for the rest of your life?

A lot of people do.

I remember working at McDonalds in high school, washing dishes for 2+ hours after the Saturday breakfast rush. Sure I got great at washing dishes, but oh the monotony. I quickly learned that specializing is boring.

But I’ve picked up a rather unfortunate truth over the last few years: Nobody wants a generalist (unless you’re Ken Jennings).

In the business world, specialization is king. Adam Smith got it started when he demonstrated the economic value of specializing tasks in a pin factory. Henry Ford mastered the concept, using specialization to build a new Ford Model-T every 24 seconds. McDonalds (where I received my first lessons in specialization) basically invented fast food by specializing their process of making burgers and fries.

But it doesn’t take a business guru to understand why specialization makes the business world turn. When you take your car in for repairs, would you rather have a dedicated mechanic work on it or a part-time mechanic, part-time trombone player, part-time scuba instructor?

Specialization wins.

So what are we variety-loving career-pursuing humans to do?

I asked this question to Steve Liddle, a computer science professor, mobile app developer, and the man responsible for scriptures.byu.edu. I’ve mentioned him before; he’s a tech-entrepreneurship enthusiast who’s always encouraging students to develop programming skills and follow tech trends.

He said that you can’t learn everything… you don’t have the time. Rather, he suggested that we ought to develop a surface level understanding of many things. Then, from that understanding, choose a few things that we really want to focus on.

It sounds simple. It is simple.

You see, if I had to give career advice to today’s youth, I’d tell them to try everything. Try writing music, drawing logos, building ramps, selling stuff, driving a boat, fixing a computer, writing news articles, designing a chair, organizing a team, charting positions of planets, babysitting, reading newspapers, keeping a budget, welding, teaching someone math, learning a language, programming, acting, designing a brochure, and anything else you can think of. I’d tell them to take on part-time jobs where they get paid to learn; to work at places like banks, offices, call-centers, government buildings and factories, doing things like tech-support, manufacturing, or secretarial work. I’d tell them to do anything to develop that ultra-broad surface level understanding of many things. Then, I’d tell them to look inward.

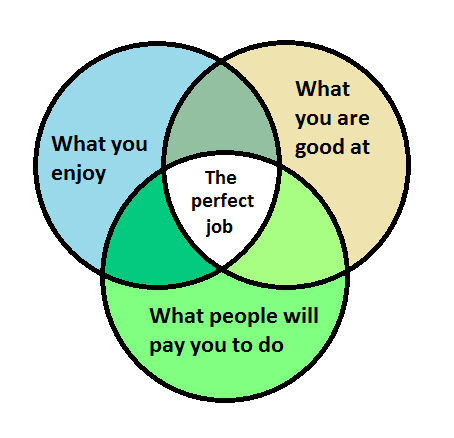

Look at what you enjoy. Look at what you are good at. Finally look at what the world is willing to pay you to do. If any career choice fits all three categories, then point yourself in that direction, and start specializing!

By doing it this way, I think career specialization can be a rewarding experience. You’ll be paid every day to dig deeper into your skill set and your interests. And you can still use the evenings to read as many Malcolm Gladwell books as your heart desires.