The unique power of games in building intuition

Miegakure is a four-dimensional video game*. To win, you must solve problems that would normally be impossible in three dimensions… like using the fourth spatial dimension to walk through walls.

How can this even be possible? The demo videos show how it works but it’s not until you play it that things start to click, at least according to one reviewer:

“Flipping through dimensions is remarkably intuitive… I shifted dimensions, messing about with this strange toy until I quickly understood most of the problems that I faced.”

Just the fact that a four-dimensional game can be “intuitive” is remarkable to me. I remember taking a math class where my professor tried to explain four-dimensional objects. She used several approaches, like math and various analogies. She even brought in a physical model of a hypercube. It wasn’t until months later, after I read Flatland, that I started to get a feel for it.

This Miegakure reviewer got a feel for it after a few minutes of playing with a video game.

Did he have a rich and detailed understanding after just a few minutes? Of course not. It was just the start of an intuition. But it was something that he could build upon in further levels of the game as he was required to navigate that world, explore its corners, and push its constraints.

I think games are the best medium out there for teaching intuition. So why don’t we do it more often?

Facts vs Intuition

Many (if not most) of the educational games out there focus on teaching facts. These are the flashcard games, the trivia games, and popular titles like Carmen Sandiego.

There’s a place for these kinds of games. Many of them are very good!

The problem with teaching facts is that anyone can find the answers to most factual questions with a Google search. Intuition, is different. Intuition helps you know what questions to ask.

This lesson was taught most clearly to me when I was working on some Physics homework with a friend of mine back in college. When we got stuck, I went to my notes while he went to his intuition. He proposed an approach, but I protested, saying we hadn’t discussed it in class. We ended up trying it and we got the correct answer.

When you focus on memorizing facts, you find yourself lost as soon as you come across a new type of problem. That’s something that happens a lot in the real world, with its near-infinite problem space, and no answers in the back of the book. Where facts give you answers to a limited set of questions, intuition gives you a direction to pursue for answering any question.

A case study

Lets look at two children’s games and see how their design leads to different learning outcomes.

Game 1: Multiplication.com

In multiplication.com’s Rooftop Ride, you control a skateboarder who skates across rooftops avoiding obstacles and collecting coins. Periodically, the game will stop and give you a math problem which you must solve before you can continue. That’s really all there is to it.

It’s a platformer game with flash-cards bolted onto it. The cards have no real connection to the game’s story. They’re like the quarters you have to insert into the arcade game to keep playing.

It’s good for kids to practice mental math but there’s a lot not to like about this approach. It focuses on memorization and regurgitation, without much of a reason behind it. What’s more, it makes the learning an obstacle to your gameplay goals. If you watch the kids play when a problem appears, they rapidly just click through the multiple-choice options until the problem goes away. It’s like they’re hunting for the “close” button on a pop-up window, because that’s basically what it is.

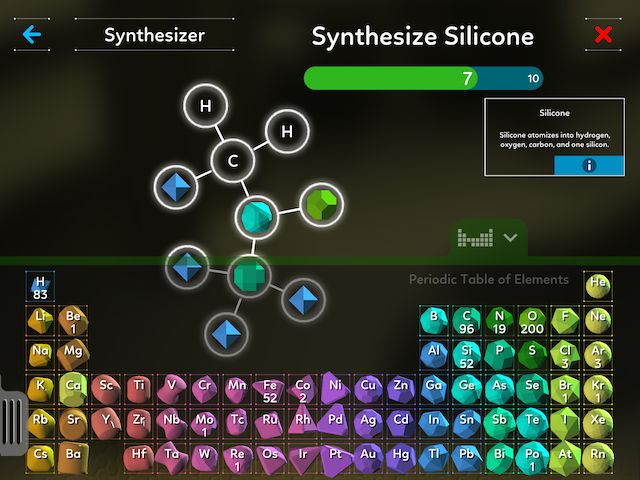

Game 2: Blue Apprentice

In Blue Apprentice (for Android and iOS), you are recruited aboard a spaceship where you must use principles of science to repair your equipment, navigate the galaxy, and stop the evil King Dullard. One of your early tasks is to forage for materials, which you break down into their atomic elements. Once you collect the elements you need, you can reassemble them into new compounds that help you on your quest.

Here, the learning material is built into the fabric of the game. The learning isn’t an obstacle… it helps you accomplish your goals. “I need silicon to build some equipment, but where do I find silicon? Does this snow contain silicon? No, I guess not. What about that quartz over there. It does! I should remember that, in case I need more silicon later.”

Perhaps the best thing about blue apprentice is this: by playing in a world that works like the real world, the kids develop intuition that translates to the real world.

It turns out that all games that build useful intuition do this:

- In Sim City 2000, the revenue model is similar to how real cities are funded, so the intuition about city economics translates.

- In Lemonade Stand, the forces driving sales are similar to the forces driving sales in the real world, so the intuition about supply and demand translates.

- In Universe Sandbox, the astrophysics is similar to real astrophysics, so the intuition about n-body gravity translates.

RollerCoaster Tycoon, Powder Toy, Factorio… all of them build intuition by mirroring the real world in some way. Pure entertainment games like Starcraft and Fortnite also build intuition. It’s just that the intuition just isn’t very useful outside of the game.

Where intuition comes from

Games are great at teaching intuition because they are experiential. Where knowledge often comes from study, intuition comes from experience.

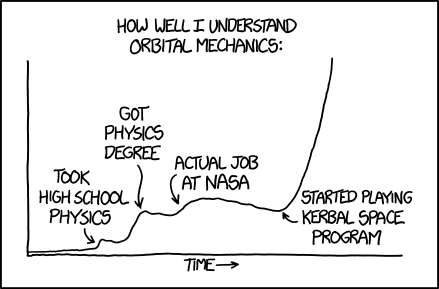

When you play a game, you live in a different world, assume a different role, and see how your decisions affect everything around you. In Kerbal Space Program, you attempt to launch rockets into orbit around an earthlike planet. Naturally, you blow up a lot of rockets on your path to understanding orbital mechanics.

But it doesn’t matter! In a game, nobody actually dies, and you don’t lose your job.

By removing the real world constraints (like death, pain, and social rejection) you can experiment, take bigger risks, and learn more rapidly as a result (which is why pilots use flight simulators so heavily in their training).

Games are the perfect medium for teaching children

Well-designed games lower the barrier of entry to a topic, so that even a child can understand the underlying mechanisms behind complex things. Consider this quote from that article on Miegakure, the four-dimensional puzzle game:

“When I asked Bosch whether players would struggle to understand his game, he replied that you didn’t have to understand gravity to know that if you throw a ball, it would go down. And he’s right. There are levels of understanding, and comprehending how this game shifts between dimensions is less important than simply grasping that it does so, and that you need to play with that to proceed.”

These “levels of understanding” exist in all disciplines and you have to understand the lower levels before higher level concepts can stick. Games like these expose children to those lower levels.

Games are uniquely capable of doing this because the game designer can break all the rules in the service of reducing complexity. They can change the laws of physics, rewind time, and display only the most relevant information. These are superpowers that can be used to break down topics and approach things in from multiple angles.

Another reason games work so well for teaching kids, is that children are masters of experiential learning.

They are programmed with an insatiable curiosity for exploring the world from as many angles as possible to see how things work. Babies put everything in their mouths, toddlers dump out boxes of food, and kids love romping in the woods. These are all attempts to understand things in the world. How they work. What they are made of. What their limits are.

As game designers, the only thing we need to ask ourselves is what do we want them to explore?

Teaching Adults with Games

But this isn’t just about teaching children. The problems in our world are increasingly complex and we can’t fix those problem unless we, the adults, understand them.

My most profound gaming experience in recent years happened while I was playing Parable of the Polygons, an online simulation-game about bias and self-segregation. At a key point in the game, I reduced the bias levels, and expected the characters to desegregate, but when I pushed “Play” nobody moved. The simulation didn’t do what I expected. How could an unbiased world still remain segregated?

That’s when it clicked. Things will stay the same unless there’s an impetus to change. In this case: a societal preference for diversity over sameness.

There was something about me being put in the scenario, committing to a plan, and watching it fail, that drove home that message.

Now, segregated cities is a big, complex problem, and sure, this simple game won’t magically fix it. But most people (myself included) aren’t going to read the 44 page research paper on the topic, and even if we did, it wouldn’t help us develop much intuition about the forces that drive segregation.

I think there are tons of opportunities to create social good by helping people learn concepts that are practical, critical, but unintuitive. Things like compounding interest, opportunity cost, diminishing returns, and others. If our society actually understood these concepts at a fundamental level, that would be a big deal!

It’s not just about developing classical knowledge either. Imagine a game where your goal is to survive while homeless. What would that do for your empathy?

Is anyone doing this?

Despite the examples I’ve shared above, I still feel like games are seriously underutilized as a tool for understanding difficult problems.

I’d love to find a game studio that identified important topics we humans need to better understand, deconstructed them, and reverse engineered them thoughtfully into games. I feel like a killer team with a shared vision and experience monetizing could put together a string of hits that entertain you while teaching important ideas. Is anyone doing this?

Maxis had a string of hits in the 90s, with its SimCity series. This inspired other simulation games like Roller Coaster Tycoon and all it’s spinoffs. But that was a while ago. What have people made recently?

One promising group I’ve been tracking is the Exporables community. They do amazing work, but it’s a pretty loose organization and the web-based interactives they often produce always seem to stop short of going mainstream.

The indie game dev scene is bigger than ever before though, so there’s probably lots of developers I haven’t heard of working on these kinds of things. If you know of any, please tell me about them in the comments.

*At the time of this post Miegakure is still under development.