The Art of the Analogy

Whether I’m speaking at a conference, talking to my coworkers, or teaching my kids, I constantly find myself grasping for analogies in conversations. They’re powerful teaching tools and great for breaking up a tough topic.

Over some trial, error, and reflection, I’ve collected some principles for building good analogies:

Know the person you are talking to

You CANNOT make a good analogy if you do not know the person you’re talking to. Ineffective speakers tend to know their topics very well, and their audiences poorly.

With analogies, you’re trying to help someone understand a foreign concept by linking it to a familiar topic. To do that, you need to know what’s familiar to them.

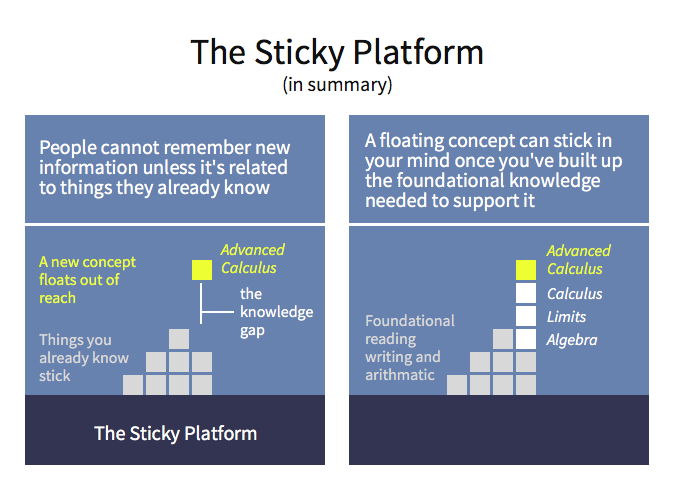

This relates to the concept of sticky platforms. You may want to check out my earlier post on the topic if you are unfamiliar with it, but in short:

When you give an analogy to a person you’re deliberately bridging gaps on their sticky platform. For example, here’s an analogy comparing the internet to a series of tubes (a joke, but you get the idea).

Find the right depth of analogy

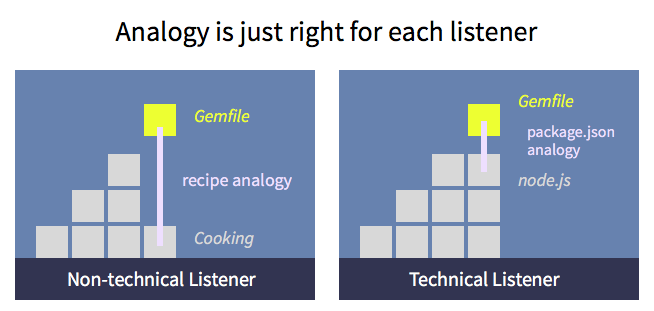

A good analogy is the perfect depth for the audience. To show what I mean, here are a few ways I could describe Bundler’s Gemfile:

- Bundler’s Gemfile is like the dependencies list in “package.json”

- Bundler’s Gemfile is like a recipe. It lists all the ingredients you need in your project.

And visually:

The second analogy is deeper because you’d use it to bridge a larger knowledge gap. But the deeper the analogy, the more detail you lose. In reality, Gemfiles are a lot more similar to package.json dependency lists than recipes.

So we’ve got a goldilocks situation when choosing an analogy: If the analogy is too shallow for a listener, they won’t understand it. If the analogy is too deep, they’ll understand but not benefit from the level of detail.

If the analogy is just right, it connects to something right on the edge of the listener’s existing knowledge. This provides as much detail as possible without losing understanding.

This concept highlights the difficulty of teaching something to a large, diverse group.

It doesn’t have to be bulletproof.

I have a very curious 4-year old, and she’s always asking me what a word means, or why she should do things. Sometimes I catch myself giving answers that are technically incorrect, but still help her understand what she’s trying to understand. For example, I recently had a conversation like this:

Me: Hey can we play after dinner? I’m busy right now. Her: What are you doing. Me: I’m working on a website. Her: What’s a website. Me: Well, it’s a computer project, but it’s tricky to make. I have to move the pieces around like a puzzle.

This is a terrible description of a website, but given the situation it’s arguably pretty helpful. She knows puzzles. She knows they can be fun, but also challenging, and that it’s hard to work on them when there are distractions (like her little brothers). The things that matter to her, like where I will be, why I need to focus, how long it will take, why I am doing it, are starting to make sense. The things that she doesn’t care about, like the technology stack, or how adults use websites, don’t need to be mentioned yet. The analogy isn’t bulletproof, but it doesn’t matter. It’s a good-enough description not because it’s bulletproof, but because it closes the current understanding gap. It helps answer the questions behind the question.

This results in an insight: there is no perfect analogy, just perfect analogies for a given situation. This is why some old analogies (like New Testament Parables) fall flat without the cultural and historical context.

Takeaways

Analogies are a powerful teaching and communication tool, one that takes some practice to get right. If you only take one thing away from this post then I hope it’s this: Good analogies come from knowing the person you are talking to. Once you know what they know, it’s just a matter of connecting the concepts.